Sprained brains, broken systems

Why men of color aren't getting the mental help they need

By Cydney Macon

“This” — he says as his hand contorts as if he’s holding an invisible knob, turning it as he continues his thought — “is like a sprained brain. Like having a sprained ankle.”

He turns his attention to the crowd hanging on his every word, including David Letterman, the host of this exclusive interview on the Netflix show “My Next Guest Needs No Introduction” which debuted in 2019.

“And if someone has a sprained ankle, you’re not gonna push on him more. With us, once our brain gets to a point of spraining,” he starts turning the knob again, “people do everything to make it worse.”

Kanye West’s bipolar disorder has been well chronicled since it seemed to begin after his mother died in 2007. Many have tuned him out because of his antics. He’s been prone to public episodes, including one in July 2020 that prompted a public statement from his wife, Kim Kardashian West, pleading for “compassion and empathy.”

At the same time, West has become an ambassador and poster child for mental health. Through his visible meltdowns and candid dialogue, West has created awareness of bipolar disorder, mental health and the vulnerability of Black men to these issues.

It’s no secret men of color face unique adversities compared to their white counterparts. Such was made abundantly clear in 2020 as the coronavirus pandemic and racial injustice uncovered the plight of Black Americans.

Men of color are two to three times more likely to experience some type of violence or trauma in their life, according to the American Psychological Association. A great imagination isn’t required to envision how embedded societal stressors and exposure to trauma can produce serious mental health effects. Just seeing a police officer could induce a panic attack.

Even with all that, rarely are men of color going to therapy. Men are much more resistant to seek help from professionals even when facing serious mental health issues such as schizophrenia, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. For a nation so centered on families, the ramifications of this phenomenon have layers of impact on society.

So, what’s keeping men of color from talking it out?

Most would venture to guess it’s a pride thing. Men are taught not to open up about their emotions but to hold them in, because it is manly to do so. That guess wouldn’t be categorically wrong. But misplaced stoicism isn’t the only culprit. Psychological wars of racism, the stigma of mental health and even socio-economic issues are barriers keeping men of color from laying on the proverbial couch and opening up.

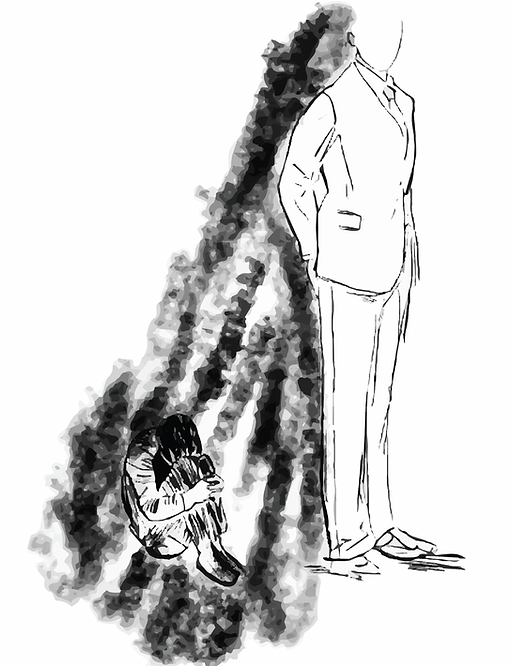

This is a cycle that has repeated itself for decades. Generation after generation, men are being beat down by the same metaphorical baton and it is leading to incarceration and suicide.

More and more programs are battling stigma and unproductive pressures with hopes of reaching this marginalized group, including at Las Positas College. Las Positas’ own Puente and Umoja programs are actively working to put a stop to this recurring cycle.

The struggles of 2020 brought mental health front and center, underscoring the urgency to address what some call an epidemic. Mental health issues, especially in communities of color, are a public health crisis. Finally, some are done ignoring it.

Machismo is definitely a factor. Showing any emotion besides aggression or anger makes a man “a pussy.” Fear of being questioned for their masculinity is causing many to swallow emotions. This creates a build-up that leads to breakdowns.

“Men just in general in American society do have a culture of not sharing your feelings,” said Eric Lee, site psychologist for the Tracy Unified School District. “They’re afraid to appear weak, to appear vulnerable — afraid of any social repercussions that may come from it.”

But experts say more keeps men of color off the couch. One major factor is systemic racism.

Demonization has been known to play a role in why men of color don’t open up about their feelings. Most men from minority communities, at some point, have been labeled lazy, dangerous, sexual predators or criminals. This trope has been so woven into American culture that, sometimes, men of color manifest these stereotypes.

The psychological warfare of racism has attacked the mind of men of color in this country so fiercely and persistently, it can normalize damaging behavior in those communities.

The article “Beyond the Stereotypical Image of Young Men of Color” in The Atlantic explains how a young Black man is seen as a “violent, drug-involved gangster; the angry, withdrawn teen; the crude, disrespectful provocateur; the unsmiling, unfeeling, untouchable thug.” These stereotypes are so pervasive, some men possessing problematic traits might not even see an issue at all. Poor anger management, for example, can be misconstrued as a positive trait.

Along with this, in general, people of color suffer from mental health care disparities. Medical News Today’s Nathan Greene, Psy.D, said, “African Americans, Latinx and Asian Americans receive treatment of mental health challenges at 50 to 70% lower rates than white Americans in this country. This is the result of failures on individual and systemic levels.”

However, according to American Psychiatric Association, men of color are much less likely to receive mental health services — excluding American Indian/Alaska Native women.

Making matters worse is a deep distrust for receiving any type of treatment.

The racism element creates an antagonistic relationship between men of color and the healthcare industry. The trust necessary to seek and benefit from treatment, to believe in the systems, is harder to come by for people who feel discriminated against or racially oppressed. Skepticism and self-reliance are preferred over handing your inner thoughts to someone with a clipboard and a soft voice.

That distrust is often compounded by another factor: therapists don’t often look like them.

In the U.S., 86% of the psychologist workforce are white, according to 2015 U.S. Census Bureau data. This creates an inherent disconnect for men of color seeking help. For many, it’s a bridge too far to expect a white therapist to understand and treat the unique hardships affecting people of color.

Nearly all psychology schools offer diversity training and cultural awareness courses in their masters programs. But the experience of living in America as a man of color can hardly be understood through a few graduate level courses.

Awareness might be less important than understanding. The website counseling.org, explains the importance of minority counselors, contend clients of color need help to “feel confident and safe in their neighborhoods, learn alternatives to violence, gain educational experiences and acquire bicultural skills needed for success in school.” These are navigational needs that figure to require experience. Yet, as of 2016, about 16% of psychologists in the United States were racial minorities, according to the American Psychological Association.

“Having therapists of color may make for a more inviting and trusting atmosphere for men of color,” said Kimberly Burks, a general counselor and co-coordinator of Umoja at LPC. “If a man of color is seeking therapy and does not see any person of color in the therapy office, he may assume that there is a lack of commonality and cultural understanding.”

Cost of therapy also creates an accessibility issue. Thervo, an online platform that connects customers to professionals of varying industries, says a session of therapy averages in the range of $60 to $120 per hour. With those parameters, weekly hour-long sessions could cost between $3,000 and $6,000 annually.

For perspective’s sake, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics survey stated in 2018 that Americans paid an average of $1,188 on cell phone service for the year. So regular therapy is like adding two or three more lines to their phone plan. A steep price for many.

Most health plans cover mental health support. But as of 2019, U.S. Census Bureau data reports 29.6 million people don’t have health insurance and about six in 10 people of color are uninsured.

Therapy is rarely advertised to low-income areas, perhaps for the financial concerns. The average counselor may not even be able to comprehend what living in low-income areas is like. According to Counseling Today, most counselors come from middle-class families of adequate means and are ignorant to the realities of poverty and the working poor, in which many men of color exist.

Burks said in some African American communities, when it comes to mental health, men will often seek out their elders, pastors, barbershops or any number of communal alternatives. These methods are often passed down through generations, practices from eras where men wouldn’t dare seek therapy. But these methods can be insufficient for the major issues people need addressed, including transgenerational traumas.

“If they don’t allow for complete healing of the mental health challenge,” Burks said, noting the cons of choosing community over therapy, “then they need to go to that next level, and that’s where the stigma comes in.”

As a result of not completely healing, challenges start to pile up even more. People of color make up about 40% of the United States population, according to the 2020 U.S. Census Bureau. However, almost 72% of prisoners are men of color, per the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Within these prisons, according to the National Alliance of Mental on Illness, they are unlikely to be diagnosed with a mental health issue and less likely to receive treatment for it.

Unaddressed mental illness from men of color is, in turn, hurting others. This can most certainly hurt their children and other family members. A study performed by doctors Paul Ramchandani and Lamprini Psychogiu, both experts affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry in Oxford, found that mental health disorders in fathers associate with increased behavioral and emotional difficulties in children. This study also included findings of fathers’ mental disorders having more distress on their families than mothers’ mental disorders.

This can also affect women as some men hold the belief that they can’t talk about their emotions. Within heterosexual marriages, women are most likely to initiate divorce because of the lack of communication. This stems from how men are usually taught not to express emotions and leaves women to take on the emotional labor of the marriage.

But hope isn’t lost as many have decided to be part of the solution of this public health concern. For the better part of 2020, the chant was “Black Lives Matter” and the plight of people of color was at the forefront of a national reckoning with race. But if it were more than virtue signaling, more than a hashtag, then society will be serious about addressing these issues moving forward. Mental health is one of those areas where actions can declare that people of color matter.

“I do think things will get better,” Burks said. “I feel right now we’re at a point of another round of awakening. I feel like ears are open and people are reviewing their hiring practices and making sure they have a diverse staff.”

The cover of West’s 2018 album “Ye” is a picture of snow-capped mountains. Scrawled on the image in neon green, in handwriting, is this simple phrase:

I hate being

Bi-Polar

It's awesome

He was on Jimmy Kimmel talking about it when it came out. His final words in the interview are about as true now as they were then.

“I think it’s important to have open conversations on mental health. Especially being Black because we never had therapists in the Black community. [People] need to be able to express themselves without judgment.”